by Peter Oundjian, Music Director

Read a message from Peter regarding COVID-19 >

When you grow up in a house full of people playing the piano, you tend to hear “Für Elise” quite a lot. As aggravating as it is to hear that opening being practiced hundreds of times over, it is actually a formidable example of Beethoven taking a seemingly banal idea and creating something of great depth. Nevertheless, beyond piquing one’s childish curiosity, it hardly hints at the true capacity of his extraordinary genius.

My father was a passionate music lover for whom playing the piano was more important than any other passion. His progress as a young man was somewhat hindered by the fact that he was a highly competitive handball player in his youth and arrived at most of his piano lessons with large welts on both hands. But he held music in one hand and sport in the other, equally as high as he could lift them. In my memory there was always music in the house, often Karajan’s newly released Beethoven symphonies.

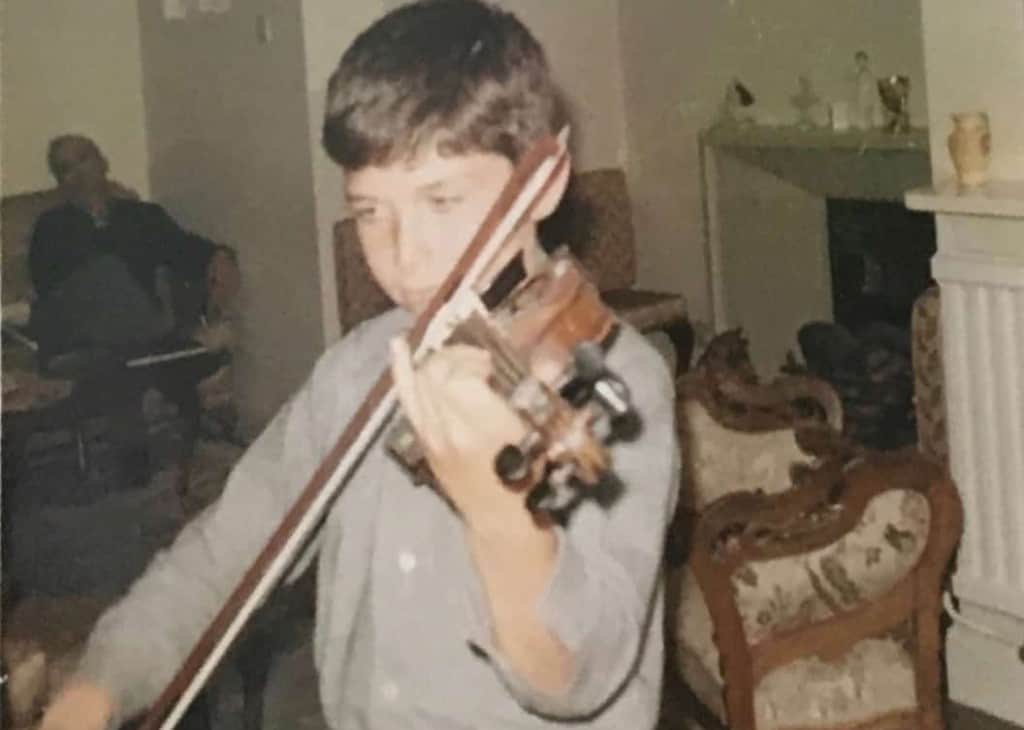

After struggling to squeeze any substantial amount of time on the piano between my father and my two sisters, I decided that the violin was a much better option. I could take it where I pleased and practice freely. It also had an immediate singing quality which seemed to suit my temperament. This gave my father a new opportunity to insert more Beethoven into the house.

Beethoven wrote 10 sonatas for piano and violin and instead of playing the usual learning repertoire it was the “Spring Sonata” of Beethoven that quickly appeared on my music stand. I remember vividly my teacher saying to me and my father that I could only play this piece once I could keep vibrato going on every 16th note in the first bar. Done beautifully, he said, that creates a glorious fluidity. Being 10 years old at the time, this sentiment made my head spin. Little did I know that a couple of decades later, some musicologists would be insisting that vibrato should never be used in music from that period, not even on long singing notes. (That’s a discussion for another blog entirely).

Other Beethoven sonatas followed and pretty soon my father was relegated to observer. My sister Marguerita had become an exceptionally fine pianist and he knew it was time to happily relinquish his post. It was one of the great joys of my childhood to rehearse and perform sonatas with my sister. We were fortunate to play many concerts together as the years progressed. We played the music of many composers, but we proudly came from a family of Beethoven fanatics.

By the time I was 16 I had also performed many concertos throughout England. A couple years later it was William Llewellyn, the director of music at my high school, who had the rather insane idea that I perform the Beethoven violin concerto during my last semester. Fortunately, the school had a vital music program and quite a good orchestra. So in the summer of 1973, while preparing for all kinds of final exams I was also mustering up the temerity to stand up and perform one of the most sublime concertos ever written for the instrument. What I didn’t know at the time was that this was the first event in a blossoming pattern: at the most significant moments in my professional life was a performance of a Beethoven masterpiece.

Soon after my last hurrah in high school, I began to play in a piano trio with two exceptional colleagues and we focused our efforts on trios of Beethoven, Schubert and Brahms. To play the “Archduke Trio” or the “Ghost Trio” at such an age opened my eyes wider to the deep sensitivity of Beethoven’s soul.

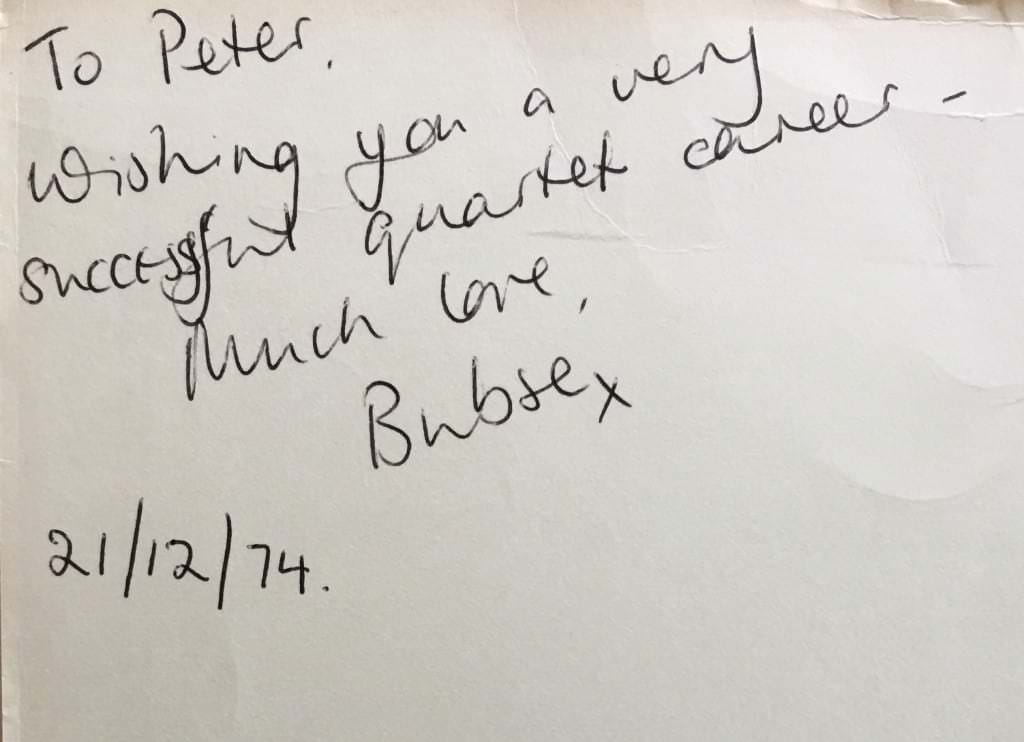

For reasons I will never quite understand, Marguerita gave me a wonderful birthday present in 1974: the complete Beethoven string quartet parts. She inscribed them:

I remember thinking it was a surprising sentiment from my sister, whom we all fondly know as “Bubse”. At the time, I had spent almost no time at all playing string quartets. Nowadays, the gift and the note feel incredibly prescient; I began my 14-year string quartet career six years later.

Once you have developed your own close relationship with a composer as honest and powerful as Beethoven, there can be no turning back. It is akin to an extraordinary friendship which never leaves you, a teacher who never stops informing you or an elder upon whom you can always rely for advice. The souls of great artists live forever in their creations. They speak to us at our own will. More than that even, they allow us to share our own passions for the magic of nature and humanity by committing ourselves to play at the height of our abilities and sensitivities when we perform their works.

Toward the end of my studies at Julliard, I was privileged once again to perform the Beethoven violin concerto with my school’s orchestra. This performance secured me professional management in New York City.

During my 14 years with the Tokyo String Quartet, we were invited to perform Beethoven cycles all over the world. Our stops included Jerusalem, Paris, Brussels, Vienna, La Scala Opera House and finally Carnegie Hall and Avery Fisher Hall. At one point, when recording the complete collection of Beethoven string quartets, it became clear that we wanted to include the extraordinary viola quintet, Opus 29. The only way we could make the recording was to agree to do it live in concert with Pinchas Zukerman as our co-conspirator. The experience of bringing that masterpiece to life without a safety net was one of the most adrenaline-filled performances of my entire life.

At the end of my chamber music career, the very last piece I ever performed with the Tokyo Quartet was Opus 131, with the exquisite Cavatina from Opus 130 as a final farewell. After more than two decades of living with the agony of severe hearing loss, Beethoven’s last works seem to reveal a vision beyond all that is good or evil. They possess a quality of spiritual fulfillment that is separate from worldly experience, one that lives in a sublime place of universal wisdom. Being a part of that music one last time was a wonderfully fitting way to end my violin career.

Many years later, when I became Music Director of the Toronto Symphony, it was time to rekindle the nostalgia of those early days at home with my father, Karajan and the 7th Symphony. It was the very first piece on my very first program as Music Director. My children were there, aged 12 and 13. Appropriately, the very last piece I conducted as Music Director in June of 2018 was Beethoven’s 9th and final Symphony. My children were there, aged 26 and 27. We’re a family of Beethoven fanatics.

To celebrate the 250th birthday of such a legend is a mighty task. But I feel as though I’ve been unwittingly preparing for it for my entire life. It’s still such a thrilling experience, not only to be a part of the performance and interpretation of a master’s great masterpieces, but to share them with a room full of fellow music lovers. It feels like the least I can do for a man who shaped my life as a musician more than any other composer did. This summer, we’ll all be one big family of Beethoven fanatics.

I hope you’ll join us,

Peter Oundjian

Music Director